The distinction between spinal cord flattening and compression represents a critical diagnostic challenge in modern neurosurgery and radiology. While these terms are often used interchangeably in clinical practice, they describe fundamentally different pathophysiological processes that affect the spinal cord’s structure and function. Understanding these differences is essential for accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment planning, and optimal patient outcomes in degenerative cervical myelopathy and related conditions.

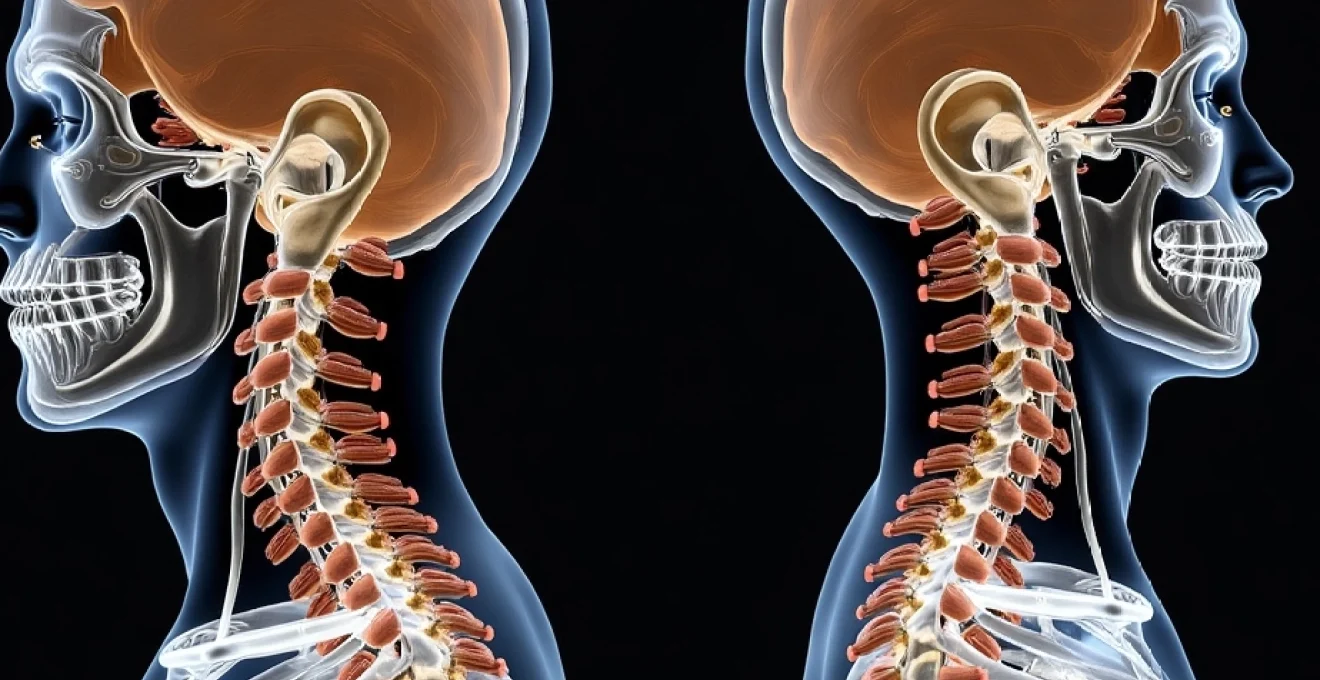

Spinal cord flattening typically occurs as a chronic, progressive process where the cord gradually loses its normal round cross-sectional geometry, becoming oval or crescent-shaped. In contrast, compression involves direct mechanical pressure that reduces the overall cross-sectional area while potentially maintaining some degree of the cord’s original shape. These morphological changes have profound implications for cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, neural tissue integrity, and clinical symptomatology.

Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging have revolutionised our ability to detect and characterise these subtle morphological changes. Quantitative measurements such as compression ratios, cross-sectional areas, and spinal cord occupation ratios now provide objective metrics for distinguishing between flattening and compression patterns. This enhanced diagnostic capability has significant implications for surgical decision-making and prognostic assessment in patients with cervical myelopathy.

Anatomical foundations of spinal cord deformation mechanisms

Normal spinal cord morphology and Cross-Sectional geometry

The healthy spinal cord maintains a characteristic elliptical cross-sectional profile, with the anterior-posterior diameter typically measuring 6-8 millimetres and the transverse diameter ranging from 10-14 millimetres at cervical levels. This natural configuration optimises the organisation of white and grey matter tracts whilst accommodating the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid space within the thecal sac. The cord’s normal morphometry varies predictably along its length, with the cervical enlargement at C5-T1 representing the largest cross-sectional area due to the increased grey matter volume serving the upper extremities.

Understanding these baseline measurements is crucial when evaluating pathological changes, as the distinction between flattening and compression often depends on subtle alterations to these normal proportions. The cervical spinal cord typically occupies approximately 40-50% of the available spinal canal cross-sectional area, leaving adequate space for cerebrospinal fluid circulation and accommodation of physiological movements during neck flexion and extension.

Pathophysiology of cord flattening: loss of Anterior-Posterior diameter

Cord flattening represents a specific type of deformation characterised by preferential reduction in the anterior-posterior diameter whilst the transverse diameter may remain relatively preserved or even increase compensatorily. This pattern typically develops in response to chronic, low-grade pressure from multiple compressive elements acting over extended periods. The dorsal compression often results from ligamentum flavum hypertrophy or facet joint arthropathy, whilst ventral pressure may arise from disc protrusion or osteophyte formation.

The biomechanical response to this chronic pressure involves gradual tissue accommodation and remodelling. Unlike acute compression, which causes immediate deformation and potential ischaemic injury, flattening allows for some degree of neural adaptation through reorganisation of neural pathways and compensatory mechanisms. However, this adaptation has limits, and progressive flattening eventually compromises neural function, particularly affecting the centrally located corticospinal tracts and dorsal columns.

Compression-induced structural changes in neural tissue

Direct spinal cord compression differs fundamentally from flattening in both its temporal evolution and structural consequences. Compression typically involves circumferential pressure that reduces the overall cross-sectional area whilst potentially maintaining the cord’s general shape. This mechanism commonly occurs in cases of severe central canal stenosis, tumour mass effect, or acute traumatic events with haematoma formation.

The pathophysiological response to compression involves immediate mechanical deformation followed by secondary injury cascades. Initial compression compromises vascular perfusion, leading to ischaemia and subsequent inflammatory responses. The degree of compression correlates with the severity of vascular compromise, with compression ratios below 0.4 typically associated with significant neurological deficits and poor surgical outcomes.

Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics in deformed spinal cord states

Both flattening and compression significantly alter cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, though through different mechanisms. In cord flattening, the preferential loss of anterior-posterior diameter creates a crescent-shaped cord that may allow some preservation of lateral cerebrospinal fluid spaces. This configuration can maintain partial cerebrospinal fluid flow, particularly in the lateral recesses, which may explain why some patients with significant flattening remain relatively asymptomatic.

Compression, conversely, tends to obliterate cerebrospinal fluid spaces more uniformly, creating a more complete block to cerebrospinal fluid circulation. This difference has important implications for the development of syringomyelia, with compression more likely to cause complete flow obstruction and subsequent syrinx formation. Dynamic imaging studies have revealed that cerebrospinal fluid flow patterns can differentiate between these two deformation types, providing additional diagnostic information beyond static morphological assessment.

Diagnostic imaging differentiation: MRI protocols and signal characteristics

T2-weighted hyperintensity patterns in flattened vs compressed cord

T2-weighted hyperintensity within the spinal cord represents one of the most significant prognostic indicators in cervical myelopathy, yet the pattern and distribution of these signal changes differ markedly between flattening and compression scenarios. In cord flattening, T2 hyperintensity typically appears as linear or flame-shaped changes extending longitudinally along the cord, often confined to the central grey matter or dorsal columns. These changes reflect chronic gliosis and demyelination resulting from prolonged low-grade pressure.

Compressed spinal cords demonstrate different T2 signal characteristics, often showing more focal, intense hyperintensity at the level of maximum compression with associated perilesional oedema. The signal changes in compression tend to be more circumferential and uniform , reflecting the global nature of the compressive forces. Additionally, compressed cords may show associated T1 hypointensity, indicating more severe tissue damage including potential cavitation or necrosis.

Research has demonstrated that the presence and pattern of T2 hyperintensity correlates with functional outcomes following surgical decompression. Flattened cords with minimal T2 changes generally show better recovery potential compared to compressed cords with extensive signal abnormalities, highlighting the importance of accurate morphological classification in treatment planning.

Sagittal plane morphometry: measuring cord diameter ratios

Quantitative morphometric analysis has become essential for objectively distinguishing between cord flattening and compression. The compression ratio, calculated as the anterior-posterior diameter divided by the transverse diameter, provides a standardised metric for assessing cord deformation. Values below 0.4 typically indicate severe compromise, whilst ratios between 0.4-0.6 suggest moderate deformation requiring careful clinical correlation.

The maximum spinal cord compression (MSCC) measurement, defined as the percentage reduction in cross-sectional area compared to normal cord dimensions, offers another valuable parameter. Flattened cords may maintain relatively normal MSCC values despite significant shape distortion, whilst compressed cords typically demonstrate proportionally greater MSCC reduction. This distinction has important implications for surgical planning and expected outcomes.

Advanced morphometric analysis using automated software tools now allows for precise, reproducible measurements of cord geometry, eliminating much of the subjective variability previously associated with radiological interpretation.

Diffusion tensor imaging for microstructural assessment

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) provides unprecedented insight into the microstructural integrity of neural tissue in both flattened and compressed spinal cords. Fractional anisotropy (FA) values, which reflect white matter tract organisation, show different patterns of reduction depending on the deformation mechanism. Flattened cords typically demonstrate selective FA reduction in dorsally located tracts, corresponding to the preferential dorsal compression seen in this condition.

Compressed cords show more generalised FA reduction affecting multiple white matter tracts uniformly. Mean diffusivity values also differ between these conditions, with compression typically causing greater increases in mean diffusivity, reflecting more severe tissue disruption and potential oedema formation. These DTI parameters correlate strongly with clinical severity and can detect subclinical tissue damage before conventional MRI abnormalities become apparent.

Recent studies have demonstrated that DTI metrics can predict surgical outcomes more accurately than conventional morphometric measurements alone. Patients with preserved FA values despite morphological abnormalities generally show better post-operative recovery, regardless of whether the primary pathology involves flattening or compression.

Cervical stenosis grading systems: developmental vs acquired changes

Contemporary cervical stenosis grading systems increasingly incorporate the distinction between flattening and compression patterns. The modified grading system proposed by recent research categorises stenosis based on both the degree of canal narrowing and the specific pattern of cord deformation. Grade 1 stenosis involves mild flattening without significant cross-sectional area reduction, whilst Grade 4 stenosis represents severe compression with marked area reduction and signal changes.

Developmental stenosis, characterised by congenitally narrow spinal canals, tends to produce flattening patterns as the cord accommodates to reduced space over time. The Torg-Pavlov ratio, calculated as the canal diameter divided by vertebral body width, helps identify patients with constitutional stenosis who are predisposed to flattening-type deformation. Values below 0.82 suggest developmental stenosis, though this measurement alone cannot distinguish between flattening and compression patterns.

Clinical presentation spectrum: myelopathy symptoms and neurological deficits

The clinical manifestations of spinal cord flattening versus compression exhibit subtle but important differences that experienced clinicians can recognise through careful neurological assessment. Patients with cord flattening typically present with insidious onset of symptoms that progress slowly over months to years. The initial symptoms often include subtle hand clumsiness, particularly affecting fine motor tasks such as buttoning clothes or writing. This reflects the preferential involvement of the lateral corticospinal tracts, which are more susceptible to dorsal compression forces common in flattening scenarios.

Gait disturbance in flattening cases tends to manifest as mild unsteadiness rather than frank spastic paraparesis. Patients may describe difficulty with balance on uneven surfaces or a sense of walking on cotton wool. Sensory symptoms are often confined to the hands initially, with patients reporting numbness or tingling in specific dermatomes corresponding to the level of maximum flattening. The progression is characteristically stepwise, with periods of stability punctuated by gradual deterioration.

Compressed spinal cords present with a different clinical profile, often characterised by more rapid symptom onset and global neurological deficits . Weakness tends to be more pronounced and affects both upper and lower extremities more equally. Bladder dysfunction appears earlier in the clinical course with compression compared to flattening, reflecting the involvement of centrally located autonomic pathways. Patients with compression may also experience more prominent neck pain and radicular symptoms due to associated nerve root involvement.

The Lhermitte phenomenon, described as electric shock-like sensations radiating down the spine with neck flexion, occurs more frequently in compression cases. This symptom reflects mechanical irritation of damaged neural tissue and correlates with the presence of T2 hyperintensity on MRI. Hyperreflexia and pathological reflexes such as Hoffmann’s sign and Babinski responses tend to be more pronounced in compression, though significant overlap exists between the two presentations.

Quantitative assessment tools such as the modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) score reveal different patterns of functional impairment between flattening and compression. Flattened cords may preserve relatively normal lower extremity function whilst showing significant upper extremity deficits, resulting in characteristic scoring patterns that experienced clinicians recognise. Compression typically produces more uniform deficits across functional domains, reflecting the global nature of the tissue damage.

Aetiological classifications and Disease-Specific manifestations

Degenerative cervical myelopathy: cord flattening mechanisms

Degenerative cervical myelopathy represents the most common cause of acquired spinal cord dysfunction in adults, with cord flattening being the predominant morphological pattern. The degenerative process typically involves multiple levels and structures, including disc degeneration, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and facet joint arthropathy. This multi-level involvement creates a pattern of circumferential narrowing that preferentially affects the anterior-posterior cord diameter.

The temporal evolution of degenerative changes explains why flattening predominates in this condition. Initial disc height loss creates segmental kyphosis, increasing contact pressure between the cord and the posterior elements. Compensatory ligamentum flavum hypertrophy further reduces the available space, creating a chronic compressive environment that allows the cord to gradually accommodate through shape change rather than acute compression.

Research has identified specific radiological patterns associated with degenerative flattening, including the bow-string effect where the cord appears stretched taut against posterior osteophytes across multiple levels. This pattern correlates with poor surgical outcomes if not addressed through appropriate multi-level decompression strategies. Understanding these degenerative mechanisms is crucial for planning surgical interventions that address all contributing factors rather than isolated levels.

Acute traumatic compression: haematoma and oedema formation

Acute traumatic spinal cord injury produces compression rather than flattening due to the rapid onset and severity of the compressive forces involved. Epidural or subdural haematomas create focal mass effect that compresses the cord circumferentially, reducing overall cross-sectional area whilst maintaining some semblance of the original cord shape. The acute nature of this compression prevents the adaptive flattening response seen in chronic conditions.

Post-traumatic spinal cord oedema contributes to the compression pattern through increased tissue volume within a fixed compartment. This secondary injury mechanism can persist for days to weeks following the initial trauma, creating ongoing compression that may respond to medical management with corticosteroids or osmotic agents. The distinction between primary traumatic compression and secondary oedematous compression has important therapeutic implications.

Imaging characteristics of traumatic compression include focal cord enlargement with associated haemorrhage or oedema signal changes. Unlike degenerative flattening, traumatic compression typically affects single levels and shows rapid evolution on serial imaging studies. The presence of associated vertebral fractures or ligamentous disruption provides additional clues to the traumatic aetiology.

Ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) impact

Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament creates unique patterns of spinal cord deformation that can involve both compression and flattening mechanisms depending on the morphology and extent of ossification. Continuous-type OPLL typically produces focal compression at the level of maximum ossification thickness, whilst segmental OPLL may create a pattern more similar to degenerative flattening across multiple levels.

The rigid nature of ossified ligament prevents the adaptive remodelling seen in softer degenerative tissues, creating sharp focal compression that poses particular surgical challenges. The K-line concept , which predicts whether the ossified mass will migrate away from the cord following laminoplasty, depends partly on understanding the compression versus flattening pattern present in individual cases.

Dynamic imaging studies in OPLL patients reveal important differences in cord deformation patterns during neck movement. Continuous OPLL may show relatively stable compression, whilst segmental OPLL can demonstrate variable compression with movement, reflecting the different biomechanical properties of these ossification patterns.

Neoplastic compression: intramedullary vs extramedullary lesions

Neoplastic involvement of the spinal cord produces distinct compression patterns depending on the location and growth characteristics of the tumour. Extramedullary lesions such as meningiomas or nerve sheath tumours create eccentric compression that may initially spare some portions of the cord whilst severely compressing others. This pattern differs from both the symmetric flattening of degenerative disease and the global compression of trauma.

Intramedullary tumours such as astrocytomas or ependymomas cause cord expansion rather than external compression, though the mass effect can secondarily compress adjacent neural structures. The imaging appearance shows fusiform cord enlargement with associated signal changes that help distinguish neoplastic expansion from external compressive mechanisms.

The diagnostic challenge increases with intramedullary lesions that show both cystic and solid components, as these can create complex deformation patterns combining expansion, compression, and secondary vascular compromise. Understanding these neoplastic compression mechanisms is essential for appropriate surgical planning and determining optimal approaches for tumour resection whilst preserving neurological function.

Surgical decision-making: decompression strategies based on cord morphology

The distinction between cord flattening and compression fundamentally influences surgical decision-making, with different decompression strategies optimised for each morphological pattern. For flattened cords, the primary goal involves restoring normal cord geometry through removal of dorsal compressive elements whilst addressing any ventral pathology contributing to the deformation. This typically requires a circumferential approach, though the specific technique depends on the predominant direction of compression forces.

Posterior approaches such as laminoplasty or laminectomy with fusion work particularly well for flattening patterns where dorsal compression predominates. The expansive nature of laminoplasty allows gradual cord re-expansion whilst preserving posterior column stability. However, surgeons must ensure adequate ventral decompression if significant anterior pathology contributes to the flattening pattern, sometimes necessitating combined anterior-posterior approaches.

Compressed cords require different strategic considerations, often demanding more aggressive decompression to restore adequate cross-sectional area. The choice between anterior, posterior, or circumferential approaches depends on the primary source of compression, but the urgency of decompression typically increases with compression compared to flattening patterns. Anterior corpectomy and fusion may be necessary for severe ventral compression, whilst posterior decompression alone rarely suffices for significant compression patterns.

Timing considerations also differ between flattening and compression scenarios. Flattened cords may tolerate delayed intervention better than compressed cords, allowing for optimisation of patient medical status before surgery. However, progressive flattening with developing T2 signal changes suggests impending irreversible injury and warrants expedited surgical intervention. The presence of dynamic compression elements that worsen with neck movement may influence the urgency of surgical timing regardless of the static morphological pattern.

Intraoperative monitoring strategies should be tailored to the specific deformation pattern, with compressed cords requiring more aggressive monitoring protocols due to their higher risk of further injury during surgical manipulation. Somatosensory and motor evoked potentials can detect early signs of iatrogenic injury, allowing immediate modification of surgical technique to prevent permanent neurological deterioration.

Prognostic implications and recovery potential assessment

The morphological pattern of spinal cord deformation carries significant prognostic implications that extend far beyond the acute surgical period. Patients with cord flattening generally demonstrate superior recovery potential compared to those with compression, reflecting the different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms and adaptive responses. This distinction has become increasingly important as surgical techniques improve and more patients achieve anatomical decompression.

Recovery patterns following surgical decompression show characteristic differences between flattening and compression cases. Flattened cords typically demonstrate gradual improvement over 12-24 months, with motor function recovery often preceding sensory improvement. The preserved cross-sectional area in flattening cases allows for more effective neural regeneration and compensatory plasticity. Patients may continue to show functional gains for up to two years following decompression, particularly in fine motor control and gait stability.

Compressed cords show more variable recovery patterns, with outcomes heavily dependent on the duration and severity of compression before surgical intervention. The critical compression threshold appears to be around 60% cross-sectional area reduction, beyond which recovery becomes increasingly limited regardless of successful decompression. Early intervention within six months of symptom onset provides the best outcomes for compression cases, whilst flattened cords may retain recovery potential even with longer symptom duration.

Age-related factors significantly influence recovery potential, with younger patients demonstrating superior neuroplasticity regardless of the deformation pattern. However, the age threshold for meaningful recovery differs between flattening and compression, with flattened cords showing retained recovery potential into the seventh decade of life, whilst compressed cords may show limited recovery after age 65 even with optimal surgical management.

Quantitative outcome measures reveal different patterns of functional improvement between these morphological subtypes. The modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association score typically shows greater improvement in flattening cases, particularly in the upper extremity motor function component. Compression cases may show more dramatic early improvements if decompression is achieved quickly, but plateau earlier in the recovery process. Patient-reported outcome measures also differ, with flattening cases showing more gradual but sustained improvement in quality of life metrics.

Long-term follow-up studies spanning 5-10 years post-operatively demonstrate the durability of surgical outcomes differs between flattening and compression patterns. Flattened cords show more stable long-term results with lower rates of adjacent segment degeneration, whilst compressed cords may experience recurrent symptoms due to ongoing degenerative processes or inadequate initial decompression. The development of delayed myelopathy at adjacent levels occurs more frequently following surgery for compression compared to flattening, suggesting different biomechanical consequences of the respective surgical interventions.

Predictive models incorporating morphological classification alongside clinical and imaging parameters now provide more accurate prognostic counselling for patients considering surgical intervention. These models account for the fundamental differences between flattening and compression mechanisms, allowing surgeons to provide realistic expectations for recovery timelines and functional outcomes. The integration of advanced imaging metrics such as diffusion tensor parameters further enhances prognostic accuracy, particularly for identifying patients with subclinical tissue damage who may have limited recovery potential despite favourable morphological patterns.

Understanding these prognostic differences enables more informed shared decision-making between patients and surgeons, particularly for elderly patients or those with significant medical comorbidities where surgical risks must be carefully weighed against expected benefits. The morphological classification provides crucial information for determining whether surgical intervention is likely to provide meaningful functional improvement or merely prevent further deterioration, considerations that are fundamental to ethical surgical practice in this vulnerable patient population.