The distinctive popping or cracking sound that emanates from your spine when you bend forward is a fascinating biomechanical phenomenon that affects virtually everyone at some point in their lives. This auditory manifestation of spinal movement represents a complex interplay between anatomical structures, fluid dynamics, and mechanical forces that occur within the intricate framework of your vertebral column. Understanding the underlying mechanisms behind spinal cavitation not only satisfies natural curiosity but also provides valuable insights into spinal health and the distinction between normal physiological sounds and potential warning signs of underlying pathological conditions.

While many people experience concern when they hear their spine crack during forward flexion, the reality is that this phenomenon is typically a completely normal aspect of spinal biomechanics. The human spine, with its sophisticated arrangement of joints, ligaments, and fluid-filled spaces, creates an environment where pressure changes and mechanical adjustments can produce audible sounds during movement. These sounds, medically termed crepitus , represent the spine’s natural response to positional changes and mechanical loading patterns that occur during everyday activities.

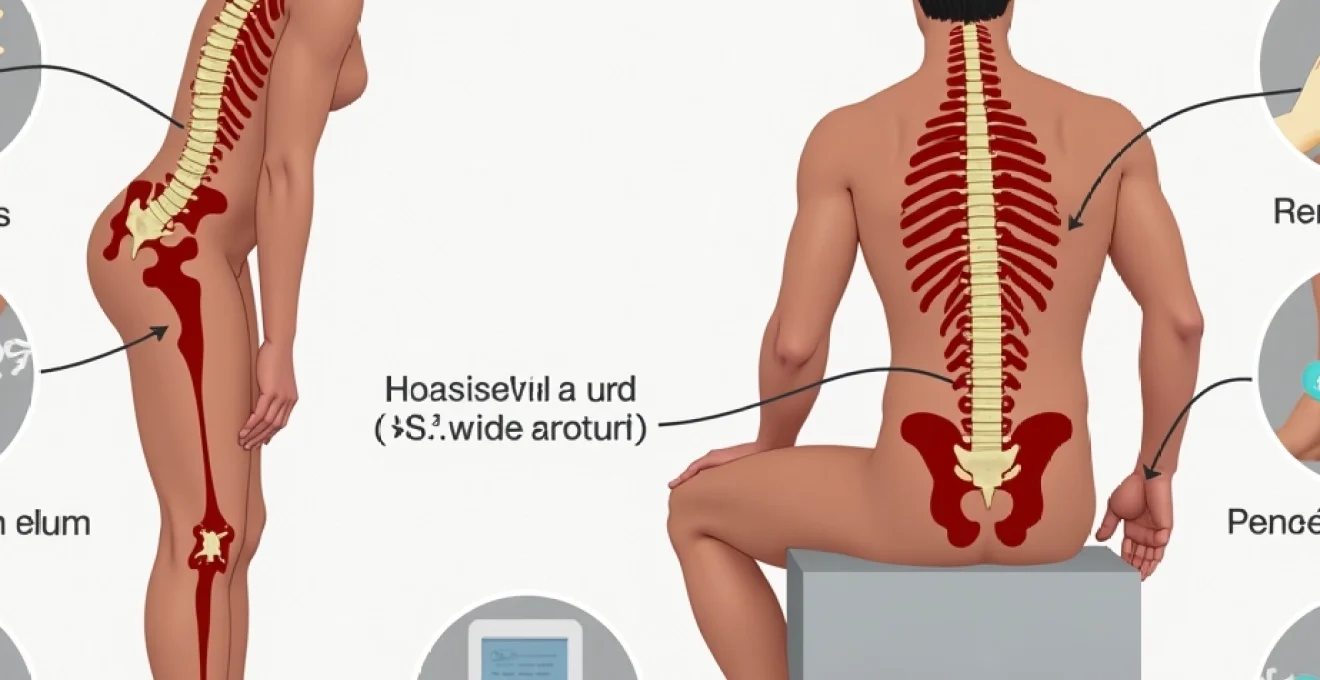

Anatomical structure of the human spine during forward flexion

When you bend forward, your spine undergoes a remarkable series of coordinated movements that involve multiple anatomical structures working in perfect synchronisation. The vertebral column, consisting of 33 individual vertebrae separated by intervertebral discs and connected by a complex network of joints and ligaments, must accommodate significant changes in loading patterns and spatial relationships. During forward flexion, the posterior elements of the spine experience stretching forces while the anterior structures encounter compressive loads, creating an environment conducive to the generation of various sounds and sensations.

Vertebral compression and intervertebral disc mechanics

The intervertebral discs play a crucial role in spinal mechanics during forward bending movements. As you flex your spine, the anterior portion of each disc experiences increased compression while the posterior annulus fibrosus stretches to accommodate the change in vertebral positioning. This differential loading creates pressure changes within the disc structure that can contribute to the audible phenomena associated with spinal movement. The nucleus pulposus, the gel-like centre of each disc, redistributes itself within the annular boundaries, potentially creating subtle pressure variations that influence the surrounding joint structures.

Facet joint movement and synovial fluid dynamics

The facet joints, also known as zygapophyseal joints, represent the primary source of cracking sounds during spinal flexion. These synovial joints contain specialised fluid that lubricates the articular surfaces and facilitates smooth movement between adjacent vertebrae. During forward bending, the facet joints undergo separation and gliding movements that alter the pressure dynamics within the joint capsule. The synovial fluid within these joints contains dissolved gases, primarily nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and oxygen, which become supersaturated when pressure drops occur during joint separation.

Ligamentum flavum stretching and spinal canal expansion

The ligamentum flavum, a series of elastic ligaments connecting the laminae of adjacent vertebrae, experiences significant stretching during spinal flexion. This stretching contributes to the expansion of the spinal canal and creates tension changes that can influence the mechanical environment of the surrounding structures. The elastic properties of these ligaments allow them to store and release energy during movement, potentially contributing to the restoration of normal joint positioning following the completion of the flexion movement.

Posterior longitudinal ligament tension distribution

The posterior longitudinal ligament, running along the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies, experiences varying degrees of tension during forward bending. This ligament helps maintain spinal stability while allowing controlled movement, and its interaction with the surrounding tissues can contribute to the complex mechanical environment that facilitates cavitation phenomena. The distribution of tension along this ligament influences the pressure dynamics within the spinal canal and may affect the timing and intensity of joint cracking sounds.

Cavitation phenomenon in synovial joints

The primary mechanism responsible for the cracking sound during spinal flexion involves a process called cavitation, which occurs within the synovial joints of the spine. This phenomenon represents one of the most fascinating aspects of joint biomechanics and has been the subject of extensive scientific investigation. Cavitation involves the rapid formation and collapse of gas bubbles within synovial fluid, creating the characteristic popping sound that many people associate with joint cracking. The process requires specific pressure and volume changes within the joint space, making it a highly predictable yet variable occurrence depending on individual anatomical factors and movement patterns.

Carbon dioxide gas bubble formation in synovial fluid

Synovial fluid contains dissolved gases in concentrations that vary based on atmospheric pressure, joint loading, and individual physiological factors. When the joint capsule stretches during spinal flexion, the volume within the joint space increases while the pressure decreases, creating conditions favourable for gas bubble formation. Carbon dioxide, being highly soluble in synovial fluid under normal conditions, becomes supersaturated when pressure drops occur, leading to the nucleation of microscopic bubbles that rapidly expand and coalesce into larger cavitation bubbles.

Tribonucleation theory and joint decompression

The tribonucleation theory provides a comprehensive explanation for the initiation of cavitation in synovial joints. According to this theory, the separation of articular surfaces during joint movement creates microscopic areas of extremely low pressure where gas bubbles can spontaneously form. These nucleation sites often occur at the interface between the synovial fluid and the articular cartilage, where surface irregularities and adhesive forces contribute to the creation of cavitation-prone environments. The rapid expansion of these bubbles generates the acoustic energy that produces the audible cracking sound.

Refractory period following cavitation events

Following a cavitation event, there exists a refractory period during which the same joint cannot produce another cracking sound, regardless of repeated attempts at manipulation. This period typically lasts between 15 to 30 minutes and occurs because the gas bubbles formed during cavitation require time to redissolve into the synovial fluid. The duration of this refractory period varies among individuals and can be influenced by factors such as joint size, synovial fluid composition, and ambient pressure conditions. Understanding this phenomenon helps explain why you cannot continuously crack the same spinal joint in rapid succession.

Acoustic properties of joint cracking sounds

The acoustic signature of joint cavitation exhibits specific characteristics that distinguish it from other joint sounds. Research has shown that cavitation produces broadband acoustic emissions with peak frequencies typically ranging from 100 to 300 Hz, with the intensity reaching levels of up to 83 decibels. The duration of the sound event is remarkably brief, usually lasting less than 5 milliseconds, which accounts for the sharp, distinct quality of the cracking sound. These acoustic properties provide valuable information about the underlying mechanical processes and can help differentiate normal cavitation from pathological joint sounds.

Biomechanical forces acting on spinal segments

The biomechanical environment of the spine during forward flexion involves a complex interaction of forces that extend far beyond the simple bending motion. Multiple force vectors act simultaneously on different spinal structures, creating a dynamic loading pattern that influences joint behaviour and the likelihood of cavitation events. Compressive forces increase on the anterior structures while tensile forces develop posteriorly, creating shear forces at the joint interfaces that can trigger the pressure changes necessary for bubble formation. The magnitude and distribution of these forces vary significantly depending on the speed of movement, the degree of flexion achieved, and individual anatomical variations such as spinal curvature and joint mobility.

During the forward bending motion, the centre of gravity shifts anteriorly, requiring increased muscular activation to control the movement and maintain balance. This muscular activation creates additional forces that are transmitted through the fascial systems and ligamentous structures, potentially influencing joint loading patterns and cavitation susceptibility. The interplay between active muscular forces and passive structural resistance creates a unique mechanical environment where small changes in movement patterns can significantly affect the likelihood and intensity of joint cracking sounds. Understanding these biomechanical relationships helps explain why some individuals experience more frequent spinal cracking than others, even when performing identical movements.

Pathological vs physiological spinal cracking

Distinguishing between normal, physiological joint cracking and sounds that may indicate underlying pathology represents a critical aspect of spinal health assessment. Normal cavitation typically occurs without associated pain, swelling, or functional limitation, and the sounds are generally reproducible under similar movement conditions. The timing of normal cracking sounds is predictable, occurring at specific points during the movement arc and being followed by a characteristic refractory period. In contrast, pathological joint sounds may exhibit different acoustic properties, occur at unusual times during movement, or be associated with symptoms such as pain, stiffness, or reduced range of motion.

The key to understanding spinal health lies in recognising that not all joint sounds indicate problems, but persistent pain accompanying these sounds should never be ignored.

Degenerative disc disease and abnormal joint sounds

Degenerative disc disease can significantly alter the normal patterns of spinal cracking by affecting the mechanical properties of the motion segment. As intervertebral discs lose height and hydration, the normal load distribution patterns change, potentially leading to altered facet joint mechanics and modified cavitation behaviour. The reduced disc height can cause facet joint compression and altered joint alignment, which may result in grinding sounds rather than the sharp cracking associated with normal cavitation. These pathological sounds, often described as crepitus , typically have a more continuous, grinding quality and may be associated with pain or stiffness during movement.

Facet joint arthritis impact on cavitation patterns

Arthritis affecting the facet joints creates surface irregularities and changes in synovial fluid composition that can dramatically alter the acoustic properties of joint movement. Arthritic joints may produce clicking, grinding, or scraping sounds that differ markedly from normal cavitation events. The presence of inflammatory mediators in the synovial fluid can affect gas solubility and bubble formation dynamics, potentially reducing the likelihood of normal cavitation while increasing the prevalence of other types of joint sounds. Additionally, the development of osteophytes and joint space narrowing can create mechanical interference that generates abnormal acoustic emissions during movement.

Spondylolisthesis-related cracking mechanisms

Spondylolisthesis, a condition characterised by the forward displacement of one vertebra relative to the adjacent vertebra, can create unique patterns of joint cracking and associated symptoms. The altered vertebral alignment affects the normal biomechanics of the motion segment, potentially leading to increased stress on certain structures while reducing load on others. This redistribution of mechanical forces can result in compensatory movement patterns that may increase cavitation frequency in some joints while reducing it in others. The instability associated with spondylolisthesis may also create clicking or clunking sounds as the displaced vertebra moves relative to its neighbours during spinal flexion.

Age-related changes in spinal cracking frequency

The frequency and characteristics of spinal cracking undergo significant changes throughout the human lifespan, reflecting the complex interplay between aging processes and spinal biomechanics. Young individuals typically experience more frequent and pronounced joint cracking due to higher joint mobility, optimal synovial fluid composition, and greater capsular elasticity. As people age, several factors contribute to changes in cavitation patterns, including alterations in synovial fluid properties, reduced joint mobility, and structural changes within the articular surfaces. These age-related modifications can result in either increased or decreased cracking frequency, depending on the balance between joint mobility and degenerative changes.

Research indicates that the peak frequency of joint cracking typically occurs during adolescence and early adulthood when joint mobility is at its highest and synovial fluid composition is optimal for cavitation. However, middle-aged individuals may experience a resurgence in joint cracking as degenerative changes begin to affect joint mechanics, potentially creating new opportunities for cavitation events. The elderly population often demonstrates reduced cracking frequency due to decreased joint mobility, although pathological sounds such as crepitus may become more prevalent as arthritis and other degenerative conditions develop.

Synovial fluid composition changes over time

The composition of synovial fluid undergoes significant modifications with advancing age, affecting its ability to support normal cavitation processes. Young adults typically possess synovial fluid with optimal viscosity, gas content, and lubricating properties that facilitate smooth joint movement and predictable cavitation behaviour. As individuals age, the concentration of hyaluronic acid in synovial fluid decreases, leading to reduced viscosity and altered flow characteristics. These changes can affect the formation and behaviour of gas bubbles during joint movement, potentially altering the acoustic properties and frequency of cracking sounds.

Cartilage degeneration and sound production variations

Progressive cartilage degeneration represents one of the most significant factors influencing age-related changes in spinal cracking patterns. Healthy articular cartilage provides smooth, low-friction surfaces that facilitate normal joint movement and cavitation. As cartilage undergoes degenerative changes, surface roughening occurs, leading to altered contact patterns and modified acoustic emissions. The development of cartilage fibrillation and eventual loss can result in bone-on-bone contact during movement, creating grinding sounds that replace the sharp cracking associated with normal cavitation. These pathological sounds often indicate the need for medical evaluation and potential intervention.

Joint capsule elasticity reduction with ageing

The elastic properties of joint capsules play a crucial role in facilitating normal cavitation events, and age-related changes in capsular elasticity can significantly affect cracking patterns. Young joint capsules possess high elasticity and compliance, allowing for rapid volume changes that promote bubble formation during movement. As individuals age, capsular tissues become stiffer and less compliant due to cross-linking of collagen fibres and reduced elastin content. This reduced elasticity can limit the magnitude of pressure changes during joint movement, potentially reducing the likelihood of cavitation events while simultaneously increasing the force required to achieve joint separation. The result may be less frequent but more forceful cracking sounds, or in some cases, a complete absence of audible cavitation despite continued joint movement.

Understanding these age-related changes helps explain why many older adults report that their joints “don’t crack like they used to” while simultaneously experiencing increased stiffness and reduced mobility. The reduction in normal cavitation frequency may actually represent a natural progression of spinal aging rather than necessarily indicating pathological changes. However, the development of new, unusual sounds or the persistence of pain accompanying joint movement should prompt professional evaluation to rule out underlying conditions that may require treatment intervention.